Legalism, consistently applied, offers certain minimal assurances and a promise of social stability. After all, a “government of laws and not of men,” as John Adams put it back in 1780, is a bulwark against the tyranny of caprice, the unpredictability of government by fiat. This is and has been a core American principle: as Tom Paine says in Common Sense (1776), “in America the law is king. For as in absolute governments the King is law, so in free countries the law ought to be King; and there ought to be no other.” This assurance is not to be tossed away lightly.

On the other hand, legalism, blindly, bluntly applied, without sensitivity to circumstance, can pose a tyranny of its own. These days, many of us have a newly piqued sensitivity, a sense of outrage even, regarding the lack of fit between legal determinations and our moral sense of what’s right. We’ve come to understand the asymmetry of power and the distortions of justice that may result when corporate “personhood” flexes its considerable muscle in our courts, our politics, and our civic life. It isn’t cynical to point out that huge, disembodied, but well moneyed corporations enjoy tremendous advantages in matters of litigation and legal settlement. Too big to fail, indeed—and often too big to be held accountable on moral grounds.

There can be a serious disconnect between what the law maintains and what we inwardly know to be right. Work-for-hire law, the legalistic basis of freelancers’ relationships to the companies for which they create work, is a case in point. Such law, now codified in the US Copyright Act of 1976, previously defined by the Copyright Act of 1909, is complex and many-sided, but does not always speak to our sense of “credit where credit is due.” The very phrase, work for hire, carries heavy, and painful, baggage in the history of comics, where corporate rights-holders have so often exerted life-changing power over the artists and writers who created the characters and trademarks that made those rights-holders rich. The case of Marvel v. Kirby—that is, the suits and countersuits between the heirs of Jack Kirby and Marvel Entertainment, Inc., as well as its subsidiaries and of course its owner, the Walt Disney Company—is a most powerful and distressing case in point.

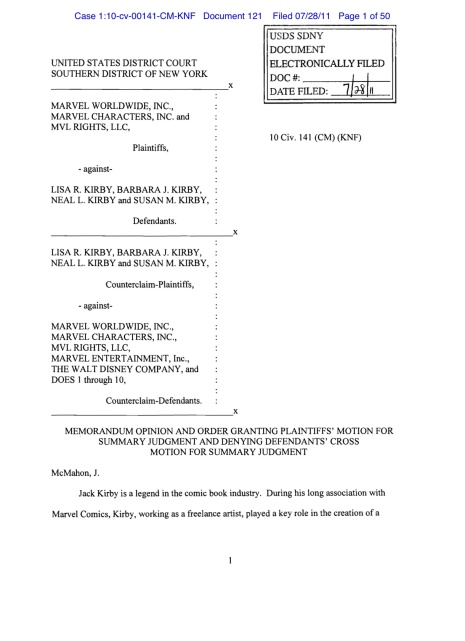

The decision in the case, rendered on 28 July 2011 by Judge Colleen McMahon of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York, denies the summary judgment sought by the Kirbys against Marvel and Disney, while granting Marvel and Disney summary judgment against the Kirbys. In effect, the decision refuses the Kirbys’ argument: that Jack Kirby’s work was not work-for-hire but rather work he conceived and offered to Marvel on his own initiative, and that therefore, under the terms of the law as it now stands, the Kirbys can terminate the copyrights held by Marvel to properties that Jack Kirby designed. The Kirbys argue, in essence, that they can reclaim the rights to the characters and concepts their father created for the company. Judge McMahon’s decision, however, throws out this claim. Basically, the decision reasserts that, even though there was no written contract between Kirby and Marvel during the period when he designed most of Marvel’s famous characters, his work for the company was simply work for hire, full stop, and that the Kirbys’ counterclaim is baseless.

McMahon’s decision is carefully parsed, and takes pains to delimit the grounds of the case, stating that it

is not about whether Jack Kirby or Stan Lee is the real ‘creator’ of Marvel characters, or whether Kirby (and other freelance artists who created culturally iconic comic book characters for Marvel and other publishers) were treated ‘fairly’ by companies that grew rich off the fruit of their labor.

Rather, says McMahon, it is strictly “about whether Kirby’s work qualifies as work-for-hire under the Copyright Act of 1909…” In this sense, the judge’s decision seeks to cordon off the case from the considerable controversy that surrounds it—controversy of which she is clearly aware—and to remove larger moral claims from consideration, in other words to ground the case firmly in legalism. This move, however, merely serves the purpose of reinforcing Marvel’s claim to the material in question, at the cost of nullifying the genuine concerns that prompted the Kirbys’ case in the first place. McMahon seeks to exclude as inadmissible the larger set of moral concerns argued by the Kirbys’ suit.

I don’t think those concerns can or should be ignored.

What made the McMahon decision possible is, first of all, the deposition given by Stan Lee; second, the judge’s decision, per Marvel’s request, simply to “strike” the testimonies of Mark Evanier and John Morrow, reducing their considered and expert judgments to hearsay; and, third, a gross misrepresentation of the relative workloads and contributions of Lee and his freelance artists under the so-called Marvel Method of production. While McMahon’s decision acknowledges the “greater opportunity for input” afforded to cartoonists under this method (16), it insists that Lee himself set everything in motion creatively, and it overestimates Lee’s editorial input, citing his veto power over the production process—“Lee retained the right to edit or alter their work, or to reject the pages altogether”—as evidence of his essential control over the process (16).

What is missing in all this is an understanding of what cartooning as narrative drawing accomplished for Marvel, especially in the hands of its powerhouse cartoonists, Kirby and Steve Ditko. As I relate in Hand of Fire,

[Lee’s] work came most often at the fore end (in initial consultation with the artist) and the aft end (dialoguing and captioning), leaving the middle to the artist. This all-important “middle” included, at the least, layout, pacing, staging, the working-out of transitions and minor plot points, and the choreographing of action: all the ingredients of sequential narrative drawing, all the elements of page design, of mise en page, composition, and reader orientation, of dramatic visual emphasis, tonal control, gesture, and expression.

In the case of Kirby and Ditko in the mid-sixties, the middle also included much more: at the least, the occasional creation of major characters out of whole cloth (e.g., the Silver Surfer, as we’ll see), the frequent introduction of supporting characters, the interpolation of new and wholly unexpected action sequences, and moments of invention that startled even Lee. What Kirby and Ditko provided to Lee, then, was not illustration but concepts, characterization, plot points, and full-fledged narrative drawing: storytelling via images, with recourse to simplification, typification, graphic expressionism, and all the myriad devices, the visual shorthand, of cartooning. Cartooning is storytelling. So, while the Marvel method lightened Lee’s workload, it made greater demands on the artists’ time, and so reinforced the artists’ sense that they were working on stories over which they could exert significant claims to ownership (creative if not legal).

[…] Ditko and Kirby grew into their own, […] eventually stamping their respective books with their design sensibilities, predispositions, even moral outlooks or glimmerings of same—all while Lee remained the nominal writer of the books. (93)

The essential point, as I go on to argue, is that Jack Kirby, who dreamed up so much of the Marvel Universe in the early to mid sixties, ought to be recognized as Marvel’s co-founder (98). He designed the bulk of the major Marvel characters, provided blueprints, in some cases layouts, for other Marvel artists to follow, and enriched the Marvel Universe through his plotting, which was, for him, inextricable from the act of cartooning. Kirby was Marvel’s powerhouse. In short, the legalism invoked by McMahon is inadequate to describing the unique situation that led to Marvel’s rise.

James Sturm puts the matter succinctly in his Slate article explaining why he is boycotting the forthcoming Avengers and other Marvel movies:

The matter of Stan Lee’s deposition is vexing (a partial transcription is available at Dan Best’s website). In essence, the deposition, repeating much that is already known from the official histories of Marvel, oversells Lee’s degree of input into the creation of the characters, saying that it was his job to “come up with the idea” and then explain it to the artists. However, it is known from numerous examples that the artists often came up with the ideas themselves, while Lee typically polished the results and made or ordered editorial corrections as he saw fit. Though I do not dispute Lee’s crucial editorial hand in the process of making Marvel comics, I do dispute—and Hand of Fire discusses this issue carefully—the claim that Lee consistently came up with the ideas, and that his artists, Kirby included, simply took direction from him. That very description mystifies what the Marvel Method of production was all about: artist-driven storytelling.

To the extent that Lee’s deposition once again blurs and distorts the history of how Marvel was created, I believe it does harm to comics historiography and scholarship. Though Lee is his own man in this matter, having himself successfully sued Marvel in the past, it is not surprising that his testimony reinforces the official Marvel history and rejects the Kirbys’ case, since any admission by Lee to the contrary could undermine his own accounts of his role at Marvel. Understandable or not, it is deeply regrettable.

In sum, the McMahon decision—now in the process of being appealed, as the Kirbys’ lawyer Marc Toberoff promised (see comments below)—buttresses Marvel’s official rhetoric and history. Regarding that history, the cartoonist Seth puts the matter in perspective, bluntly perhaps, but, I believe, rightly:

The corporate lie about Kirby’s role in the creation of all those characters is abhorrent. It’s a bold faced lie. Everyone knows it’s a lie. No one is fooled. Everyone lying for the company should be ashamed. Stan Lee should be ashamed. What the Marvel corporation is doing might be legal but it certainly isn’t right.

Dead on target: it might be legal but it certainly isn’t right. There is nothing in work-for-hire law that adequately accounts for the creation of Marvel Comics. Jack Kirby, and in effect his family, gave prodigally to Martin Goodman’s company, and that giving laid the foundation for the Marvel Universe. It’s shameful that the decision handed down last July hedges and obfuscates this issue under a fog of cold, morally tone-deaf legalism. If the law is king here, it is a tyrant.

Since last summer fans and commentators have parsed the legal merits of the Kirbys’ case, some with the usual careless defensiveness (that’s how capitalism works, didn’t you know?), some delicately. Seemingly reasonable arguments have been put forth supporting Marvel’s case and Judge McMahon’s interpretation. For example, Terry Hart’s Copyhype, a blog on copyright and intellectual property law, seeks to summarize and clarify the case in a way that affirms the judge’s decision, concluding that it is “on solid legal ground and consistent with previous cases.” Perhaps I’m fortunate in that I do not have to make my own decisions purely on such grounds, and can stand outside of the legalistic framework. In any case, I do not agree that the issue begins and ends with a legalistic understanding of work-for-hire law as codified in 1909 or 1976. I think it properly begins and ends with moral questions, with which McMahon’s decision manifestly fails, or rather refuses, to engage.

I support the petition authored by Bryan Munn, now circulating online, which calls for acknowledging Jack Kirby’s unique role in the foundation of Marvel and compensating his family accordingly. What the petition says, I am following:

Until such a time as Marvel can make things right with Kirby’s legacy and Kirby’s family and heirs, we will refuse to purchase any Marvel product, including comic books, movies, toys, or games. We ask Marvel, Disney, and its shareholders to act ethically and morally in this situation, just as their characters would.

In my case, I interpret this boycott to include new Marvel-branded product, including republications, repackagings, and adaptations of old material, and also product not branded “Marvel” but published by Marvel, such as the creator-owned Icon comics. I understand that there may be smart people who disagree with this stance, but I know that, to me, underscoring Kirby’s role as Marvel’s co-founder means more than any pleasure I might get from those comics, films, and other products.

There is legalism, and then there is justice.

I welcome thoughtful, considered responses to the issue of Kirby v. Marvel.

A couple of things. The judge did not strike the declarations of Sinnott, or Steranko.

Only fragments of the depositions were published. Marvel asked for and was granted a protective order over the depositions early in the case.

http://docs.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/new-york/nysdce/1:2010cv00141/356975/34/

Toberoff’s deposition of Lee was on Dec. 10, 2010. The Disney deposition was on May 13, 2010. Disney combined fragments of the two depositions into one attachment in their filing without pointing out their page 101 was page 396 of the Dec. 10 testimony. So you can see right there Toberoff’s deposition alone was at least 396 pages if you assume page 396 was the last page. If the May 13 deposition was of similar length then we have seen very, very little of Lee’s testimony and only those portions agreed to by Disney.

BTW my favorite portion of the judges ruling was this bizarre aside on page 18:

“In that first issue, The Hulk had gray skin. However, the printer could not provide a consistent shade of gray throughout the book… By the second issue The Hulk had acquired his now-recognizable green skin… Lee picked the color green because there was no other green hero at the time.”

At times the judge comes across as Lee’s press agent:

page 14: “Lee reviewed every artist’s work before publication.”

page 15: “During Lee’s early years as art director/editor, either he or another writer prepared detailed ‘scripts’….” (She mentions Larry Lieber here.)

page 15: “Predictably, Lee could not write enough stories to keep up with the artists, who wanted new stories to draw as soon as they finished an assignment… So to insure that his artists always had an assignment, Lee invented what became known as the ‘Marvel Method’…Under the Marvel Method Lee would not write a detailed script for a story before assigning an artist to draw it. Instead, at a ‘plotting conference,’ or in a ‘plot outline,’ Lee gave the artist the general contours of the story he had in mind: an outline of the plot, a description of the hero, and suggestions for how the story should look.”

page 17: “Like other artists who worked for Marvel at the time, Kirby created his artwork based on plot outlines or scripts provided by Lee.”

The judge did not strike the declarations of Sinnott, or Steranko.

You’re absolutely right, Patrick. The “motions to strike” are detailed in pages 4-13 of McMahon’s decision, and page 6 clearly states:

My error, due to haste, for which I apologize. I’ve corrected the text accordingly.

(For the record, everyone, in the seventh paragraph above my original version mistakenly referred to the judge’s decision, per Marvel’s request, simply to “strike” the testimonies of Mark Evanier, John Morrow, Joe Sinnott, and Jim Steranko, reducing their considered and expert judgments to hearsay. As Patrick points out, the reference to Sinnott and Steranko was wrong.)

I appreciate your eagle eye there!

BTW, Patrick, I’ve taken a few liberties with the editing and formatting of your comment, in order to make it match the text of the judge’s decision precisely. I hope that’s fine with you. Of course we want to be exact in these things!

Charles, I always appreciate editing, I type this stuff out surrounded by two kids, three old dogs, two cats, and five chickens in the yard.

Ha! That’s a lovely image. Thanks, Patrick.

Thank you for taking a stand here. As an historian and an academic. your voice will certainly resonate. The treatment of Kirby in this situation is so exasperating and baffling in its negative implications that it rivals the Chancery suit from Dickens’ Bleak House.

Thanks, Norris. Agreed, and well put.

Steve Bissette had a great comment recently. As Steve points out Kirby’s creative contribution was reduced by Stan Lee to the role of, “…a meat puppet, a pair of lackey hands, moving graphite around…”

“…according to Marvel, STAN LEE is the primary creator of ANYTHING Jack Kirby worked on, right? I mean, that WAS and IS the legal argument involved with that 2011 judgment. But: ‘Quesada: From the Marvel side of things, we absolutely agree that Gary made a significant contribution to the creation of Johnny Blaze/Ghost Rider. That has never been under contention. But Gary didn’t do it alone. Mike Ploog, the original artist, was a co-creator. Other people contributed as well, including Roy Thomas and Stan Lee. There were many individuals present at the time of Johnny Blaze’s creation who disagree with the claim that Gary was the sole creator.’ So, see, if it benefits Marvel, the writer, and especially writer/editor, IS the primary creator. The artist is just, like, a meat puppet, a pair of lackey hands, moving graphite around at the behest of Marvel. But when it doesn’t… Work-for-hire, as a principle, invites, even demands, such rationales.”

Most of this comes down to Marvel’s concern that Kirby was never under contract with Marvel 1958-63, not even with something like the stamped checks. Marvel had to argue Lee was the sole creator of characters, and gave them to Kirby. If you read the Judge’s ruling it’s clear Lee also claims to have helped design the visual look of the characters.

“Lee gave the artist…a description of the hero, and suggestions for how the story should look.”

If Kirby was pitching characters to Lee which Lee could accept (The Hulk) or reject (Kirby’s Spiderman), then it would show Kirby was working on spec with no expectation his pitches would be purchased. That’s why James Quinn had Lee say (as pointed out by Toberoff) he always paid “artists” for rejected work. This came right after Toberoff has questioned Lee about Kirby’s Spiderman. That portion of Lee’s testimony was not part of the scant bits Disney chose to include in their redaction of Lee’s deposition. We only know Toberoff questioned Lee about Kirby’s Spiderman because Toberoff mentioned it in a letter to the judge where he complained Quinn appeared to have coached Lee right after Toberoff finished his questions, and then Quinn had Lee return and give the testimony where Lee said Kirby was paid for the rejected Spiderman pages.

Toberoff countered Lee’s testimony with sworn declarations from Gene Colan, Dick Ayers, and Joe Sinnott, who all swore under penalty of perjury that Marvel never paid them for rejected work.

Of course the conventional wisdom here is that Lee did work closely with Kirby in the early days of the Marvel superheroes, conferring, jointly brainstorming the characters, and crafting plot outlines. Yet that would seem to be denied both by Lee’s self-serving testimony on the one hand, and, on the other, by Toberoff’s case, which says that Kirby came up with the ideas alone, on spec.

To some extent, Hand of Fire reinforces the conventional wisdom, casting Kirby and Lee as active collaborators during the early, founding days on the FF, for example. Note, however, that I tread lightly on those claims (e.g., regarding Lee’s oft-reprinted plot outline for FF #1), because I am not fully convinced, and cannot confirm them. That’s an instance where I have to go on the secondary literature, which is foggy and conflicted.

I cite another Lee plot outline in my book, mainly to show how little it actually contains.

I have never bought, and my book does not endorse, the idea that Lee came to Kirby with his own independently conceived ideas and asked Kirby simply to illustrate them. I’m certain that it did not happen like that, because there’s too much of Kirby in the very conception of those characters. So I am skeptical of any scenario that puts Lee in the driver’s seat conceptually.

Of course it’s clear that by the mid-60s both Kirby and Ditko were plotting whole comic books with minimal to no meaningful initial input from Lee. My sense is that things were different in, say, 1961-62. The case that Toberoff presents, however, argues for Kirby working up the characters solo from the very start.

The matter deserves a stronger, clearer light, obviously. What I’m sure of is that those characters and story-worlds were shaped by Kirby from the bottom up, Lee’s claims to the contrary notwithstanding. What I still wonder about is the extent of their dialogue in the early days.

As a scholar, I have no desire to build Stan Lee up, or tear him down. Would that we could sort the historical record without the haze generated by partisanship. But when it comes to the legal case, of course partisanship is what I feel.

Charles, during those years Marvel was literally a “one-man-office.”

The early 60’s bullpen didn’t exist. It was Stan alone in a tiny cube; the moveable office wall system (standing movable partitions common in ’50’s office buildings) closing in on him. Picture the tiny office in the film BRAZIL.

Drew Friedman: My dad (Bruce Jay Freidman) actually worked at Magazine Management, which was the company that owned Marvel Comics in the fifties and sixties, so he knew Stan Lee pretty well. He knew him before the superhero revival in the early sixties, when Stan Lee had one office, one secretary and that was it. The story was that Martin Goodman who ran the company was trying to phase him out because the comics weren’t selling too well.

Harvey Kurtzman based his great story “The Man in the Gray Flannel Executive Suite” on his time working for Goodman, and Stan Lee in the late ’40s. Kurtzman met his wife Adele who was Stan Lee’s girl Friday in the late ’40s while working for Timely.

Kurtzman’s Martin Goodman stand-in is a character named Lucifer Schlock. If the story has a core of truth, Goodman/Schlock wouldn’t fire an editor. Instead he would try to make them quit by subjecting them to humiliation, marginalizing them, and taking away their staff. This sounds like what Bruce Jay Friedman says was happening to Stan in the late 50’s. In the story Lucifer Schlock drives a long-time editor to suicide. When the editor takes his own life by leaping out a window Schlock calls his secretary.

LS: Mr. Eolith has just jumped out the window. Notify the proper authorities immediately.

Miss Verifax :l’ll notify the police, and the hospital is there anything else?

LS: What about the accounting department!!! You don’t think I’m going to keep a dead man on payroll! First things first Miss Verifax!

Dick Ayers: Things started to get really bad in 1958. One day when I went in Stan looked at me and said, “Gee whiz, my uncle goes by and he doesn’t even say hello to me.” He meant Martin Goodman. And he proceeds to tell me, “You know, it’s like a sinking ship and we’re the rats, and we’ve got to get off.” When I told Stan I was going to work for the post office, he said, “Before you do that let me send you something that you’ll ink.”

Kirby had first returned to Timely/Atlas in 1956 shortly before starting to work for DC later that same year. In 1956 Goodman was publishing dozens of comics books every month. In 1957 Goodman experienced a self-inflicted distribution misadventure. Page rates were slashed, and Goodman purchased very little new material for several months. Kirby began selling more work to DC. In 1958 after a dispute with DC Kirby again began selling work to Goodman, and found a very different “office.”

Jack Kirby: They were moving out the furniture.

Larry Lieber: It was just an alcove, with one window, and Stan was doing all the corrections himself; he had no assistants. Later I think Flo [Steinberg, secretary] and Sol Brodsky [production manager] came in.

Flo Steinberg: After a couple of interviews, I was sent to this publishing company called Magazine Management. There I met a fellow by the name of Stan Lee, who was looking for what they called then a gal Friday…. Stan had a one-man office on a huge floor of other offices, which housed the many parts of the magazine division…. Magazine Management published Marvel Comics as well as a lot of men’s magazines, movie magazines, crossword puzzle books, romance magazines, confession magazines, detective magazines….

Romita: There was a huge bullpen when I worked there in the ’50s. And this was even after he’d laid off a lot of people. Gene Colan, John Buscema, John Severin (who had all been on staff). They were gone by the time I got there. When I went back (1965) there was no bullpen at all. There were only three people there Stan, Flo, and Sol. When Flo was hired 1964 it had been only Stan with Sol working in the office part time as freelance production help.

Kirby: I had to make a living. I was a married man. I had a home. I had children. I had to make a living. That is the common pursuit of every man. It just happened that my living collided with the times. Circumstances forced me to do it. They forced me. There wasn’t a sense of excitement. It was a horrible, morbid atmosphere. If you can find excitement in that kind of atmosphere it was the excitement of fear.

Thanks for this excellent anthology of supporting material, Patrick. Of course all this is rehearsed in Hand of Fire, including the shrunken, almost comatose nature of Goodman’s comics line in the late 50s, the nature of his larger Magazine Management operation, Kirby’s financial desperation during that period, and the account Kirby gave in his long interview in TCJ (re: the near-closing of Lee’s office, the furniture being moved out, etc.). The Friedman memoir (“Even the Rhinos Were Nymphos”) is particularly helpful in conjuring the scene at Magazine Management.

It’s absolutely clear to me that the former Atlas would never have become the “Marvel” we know, nor even survived, had Kirby not come back and put shoulder to the wheel. The story Lee tells about wanting to do comics “his way” (the epiphany that he says led to FF) does not persuade me. Something else had to be happening then—and that something else was Kirby.

In 1986 Lee told THE VILLAGE VOICE:

Lee really does not seem to understand, or at least will not admit, the ramifications of the Marvel Method.

I believe my argument in Hand of Fire counters Lee’s well enough, so I’ll let this stand without much further comment. Just two things: (1) In comics, breaking the story down “to determine what each drawing [will] be” is a kind of composing, i.e., writing. As Kirby once said, “I’ve been writing all along, and I’ve been doing it with pictures.” (2) You cannot “inject” personality merely by dint of scripting dialogue. The drawings were already imbued with personality.

Nuff said!

Regarding Marvel v. Kirby, Dan Best has just posted the appellants’ Opening Brief, i.e. the opening brief in the Kirbys’ appeal of the July 28th decision:

http://ohdannyboy.blogspot.com/2012/02/marvel-vs-kirby-appellants-opening.html

Toberoff’s brief takes a “Jack” hammer to the judge’s ruling. I hope everyone interested will reread the judge’s ruling with care, as well as the Toberoff brief.

This is not, and never was about “fairness.” Fairness in the sense that the law is clearly against Kirby, but Marvel should do the charitable thing and give the peon a handout. As Toberoff points out this was about “Marvel’s case stands or falls on (Lee’s) testimony.”

The judge said it, Toberoff quoted it, but all I hear is people saying, “Brush a few crumbs off the table for the dogs why don’t you.”

Charles, I must say after meeting you, a couple of years at SDCC, and reading your book, I was impressed with your total grasp of this weighty legal argument. Now, after reading your most recent piece, about the settlement, I think you are the only person that has communicated it in such a way, that it does not seem so complicated, anymore. The one thing, that is for me, the best argument, within the argument, is the artist driven, “the script comes after the art” standard that even Stan the Man espoused, for decades, until Marvel’s lawyers basically told him to shut the hell up. Thanks for this lucid explanation for all of us Jack Kirby backers, on this profound resolution.

Bill, thanks for these kind words. I’m glad my writing has been helpful. The issue has been so complicated—yet on a gut level, so simple to me, and so urgent—that it’s been hard to stay on top of it. This past summer, for example, when news of the SCOTUS conference and the amici briefs came out, I was so busy dealing with other upheavals that I couldn’t blog that news in a timely way. Now that the settlement has been reached, I’ve been trying to see everything in hindsight, in perspective, and to reconstruct the whole timeline for my own benefit. Again, glad to know the effort has been a help to you too!