Kirbyvision: A Tribute to Jack Kirby, an exhibition now showing at the Corey Helford Gallery in Los Angeles, lovingly registers Kirby’s impact on contemporary comics, media, and culture. Curated by the Jack Kirby Museum and Research Center, in collaboration with the Helford, the show offers for sale new or recent works by more than seventy artists inspired by Kirby, alongside a historical exhibition of Kirby originals that outlines his style, techniques, and key creations. Together, the historical exhibit and contemporary tributes reaffirm Kirby’s continuing influence. I urge comics and Kirby fans anywhere within a day’s travel of Los Angeles to pay it a good, long visit (alas, it remains open through just Saturday, August 3—would that it could stay longer!). The show is free and open to the public.

I’ve experienced Kirbyvision twice myself, and hope to again. Having curated the 2015 CSUN show Comic Book Apocalypse: The Graphic World of Jack Kirby (to which the Museum contributed substantially), I have a sense of what it takes to contextualize Kirby’s art for gallery visitors. I greatly admire what the Museum has accomplished here. Of course, I can hardly be objective, since I’m a Kirby diehard (and serve on the Kirby Museum’s Board of Advisors), but I hope that the following description gives the flavor of the show and helps document it for posterity. Do know my bias, going in, but also know that this is a show you should see if you love comic art.

Kirbyvision opened Saturday, June 29, with a bustling reception that brought out diverse artists, collectors, fans, and members of Kirby’s family. The buzz and shared happiness that evening were fairly electrifying. I was glad to be in happy company, and enthralled from the get-go. The show is an eye-popping design experience and a triumph for the Kirby Museum, which has carried the torch since its founding in 2005 and began holding pop-up exhibitions in 2013. For years, the Museum has been seizing opportunities to demonstrate just what it can do—and I think this show, more than any previous event, does that wonderfully. So, here’s my report:

The Corey Helford is in eastside Los Angeles, by the L.A. River, within a district that feels postindustrial. Around it stand imposing buildings festooned with a mix of graffiti and bespoke murals. My wife Mich and I have been visiting L.A. galleries lately, and they tend to be in repurposed settings like this. The Gallery building, a block of brick surrounded by fences, runs to 12,000 square feet. Its main gallery, a vast openness, takes up about 4500 of that, while two other galleries open off to the side. Unsurprisingly, all of these are whitewalled, cement-floored, and adaptable artspaces. Kirbyvision currently occupies most of the building, though one gallery holds an exhibition by painter Bennett Slater (who renders dolls and other commercial icons with Old Master precision).

Slater, an artist frequently shown at the Corey Helford, epitomizes the gallery’s New Contemporary slant. The Helford seems to favor Surreal, Pop-inspired figurative work blending lowbrow references with exacting technique and high gloss. It has a Hi-Fructose and Juxtapoz vibe, with nods to street art and impish personal riffs on commercial design. Kirbyvision mostly fits into that wheelhouse. The bulk of the show consists of eighty-plus homages to Kirby (or genres and brands he is known for). The work on view embraces various media and ranges technically from rowdy handmade-ness to industrial sheen. Paintings and drawings are the main things, though there are also collages, digital prints, and sculptures.

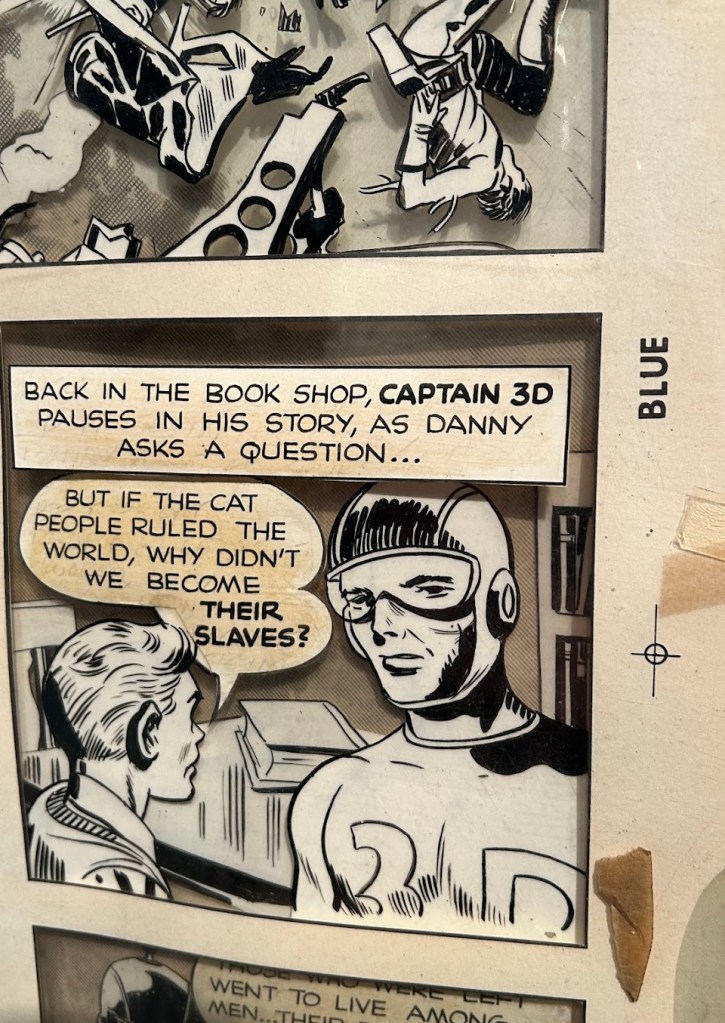

If the works on offer are mixed, the total design of Kirbyvision brings unity. The show’s main design conceit is the idea of 3-D vision, with nods to Kirby and Joe Simon’s single issue of Captain 3-D from 1953 (a then-faddish 3D comic published by Harvey). At the outset, a dividing wall in the main gallery’s entrance (which visitors skirt around to enter the gallery proper) bears a triptych of images from that comic, dramatically scaled up in very effective 3-D separation. Scanning that wall from a few paces back with the anaglyphic (red and blue) 3-D glasses freely provided by the gallery imparts a strong sense of movement. The 3-D elements represent a collaboration with stereoscopy expert Eric Kurland (founder of 3-D Space), whose gift for this kind of work can be felt throughout the show (so keep those glasses with you).

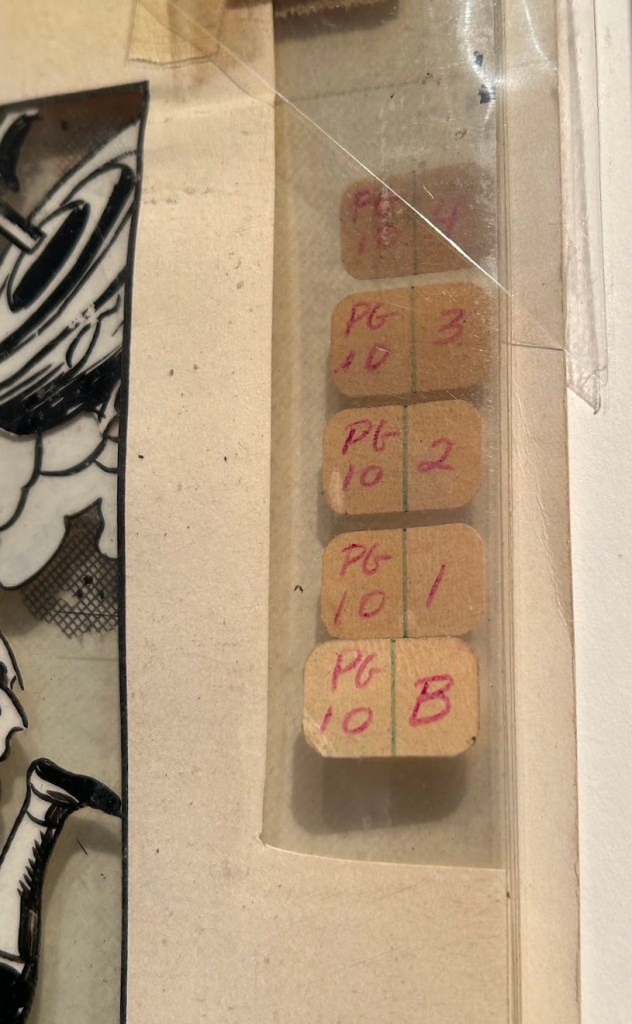

In effect, the 3-D hook gives Kirbyvision a brand identity (while suiting the Helford’s retro Pop sympathies). Displayed near the gallery entrance are two originals from Captain 3-D itself that hint at the laborious processes used to make 3D comics in the early Fifties. Those originals consist of Kirby-drawn elements separated onto layers of acetate, as well as shaded backgrounds on what appears to be Craftint paper. The originals are well preserved, yet their aged patina contrasts with the gorgeous wall-sized reproductions. This is both instructive and cool. Also displayed here are the published Captain 3-D and Kirby’s later 3D collaboration with Ray Zone, Battle for a Three Dimensional World (1982). Further in, attentive visitors will find an oversized reproduction of the entire Captain 3-D comic book (again, hold on to your glasses!).

Other savvy design elements pop up across the show. A library of Kirby books is on sale in the lobby, courtesy of retailer Golden Apple Comics (and Kirby-related videos also play there, sotto voce). Just to the right of the 3-D dividing wall you’ll find a mockup of a period newsstand filled with comic books that, I gather, are free for the taking. On the night of June 29, the comics were vintage Kirby comics; for example, I saw friends leaving with mid-1970s issues of Kamandi (though when I revisited on July 12, the newsstand carried only Archie). Once you come around the dividing wall and into the main gallery space, you’ll find, on the wall’s flipside, a big mural of Kirby’s Galactus painted by the artist Skinner (seemingly based on a splash from Thor #167 by Kirby and Vince Colletta, 1969). Facing that mural, in the gallery’s center, is filmmaker and modelmaker Martin Muenier’s life-sized rendition of Thor’s Mjolnir, magnetically affixed to its anvil-like pedestal, which proved an irresistible interactive element for many visitors (myself included). In short, moving through this space is a lot of fun.

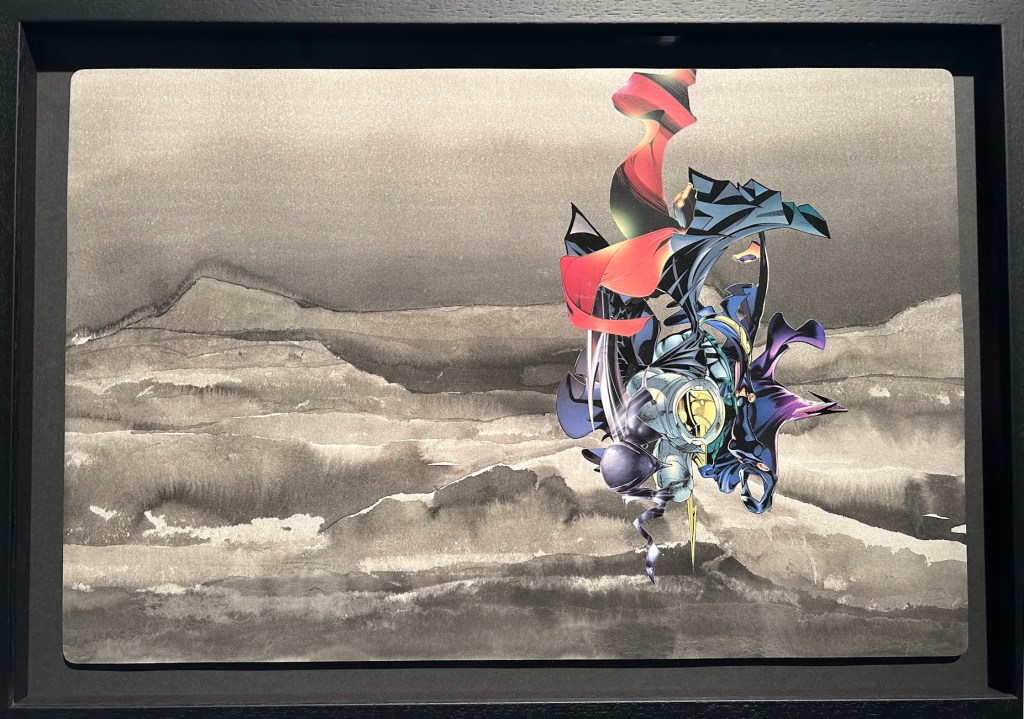

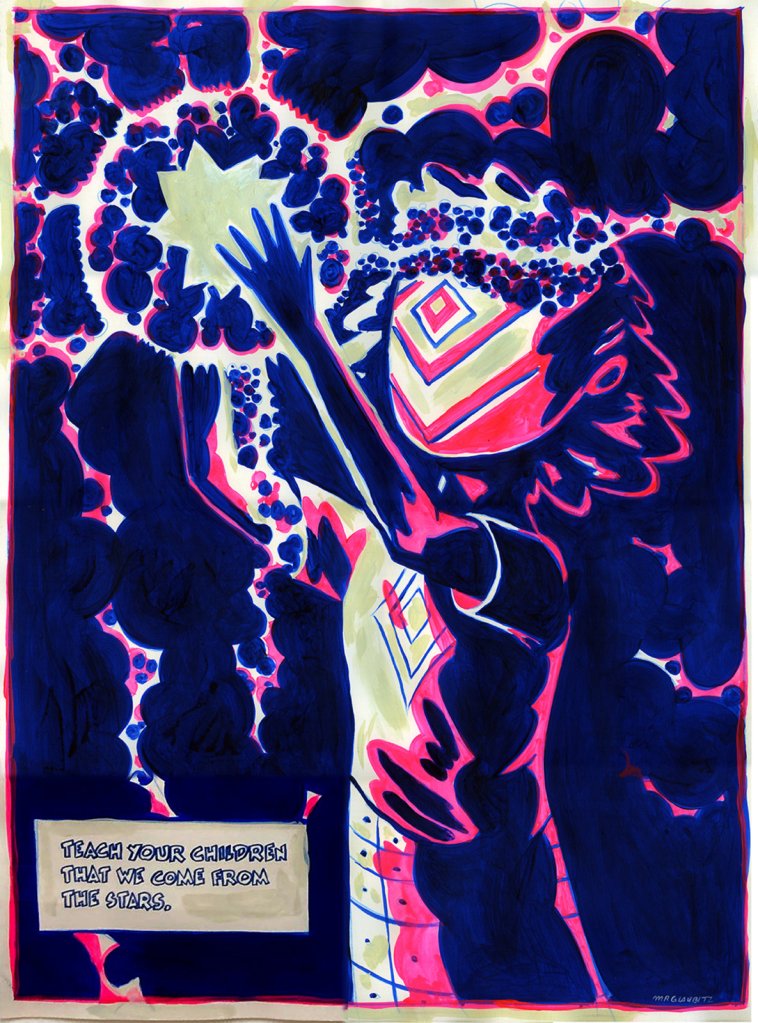

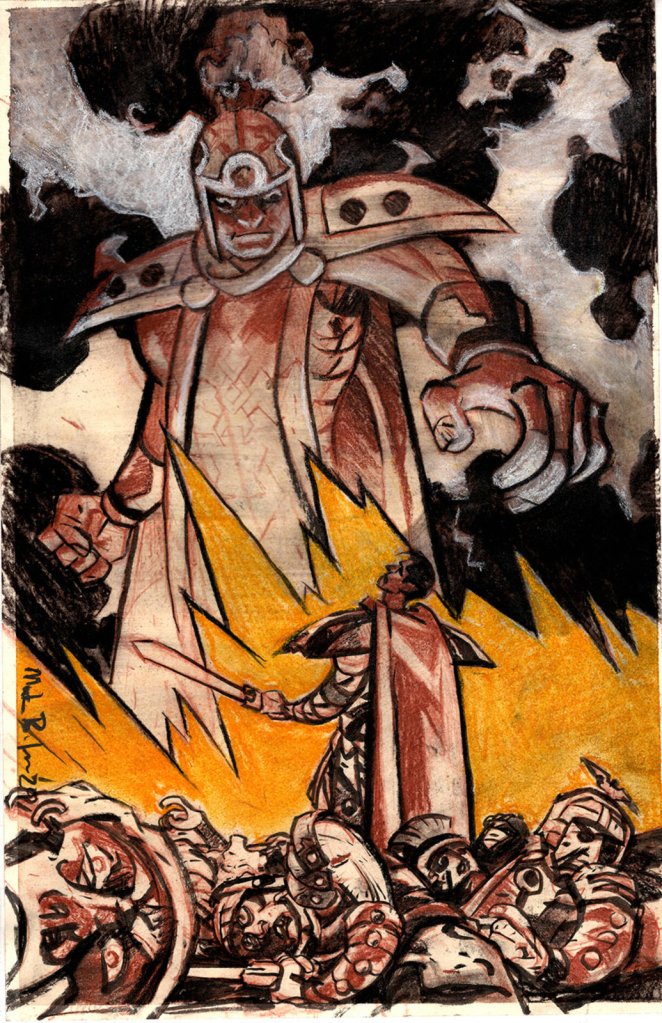

Most of Kirbyvision is presented in traditional white-cube style, with works on the walls proceeding clockwise. Some of the works are homages or détournements of recognizable images by Kirby, such as Patrick McDonnell’s Captain America canvas, The Last Superhero, or Tom Morehouse‘s collage, Kirby Crime, which mashes up images culled from decades of Kirby’s work in crime comics. On the other hand, some works are looser evocations of theme or genre that do not strive to be graphically Kirbyesque, such as Erika Sanada’s miniature ceramic Versus, with its two cute, rabbit-like critters locked in combat, or Aaron Noble’s collage The New Man, which blends swirling, cape-like elements, culled from various drawings of superhero costumes, into a hovering, abstracted shape. Some works cleave to a stylized naturalism familiar from mainstream comic books, while some are more explosively graphic, like Charles Glaubitz’s crackling acrylic and gouache drawing Teach Your Children That We Come from The Stars. Some are sober, but others playful, like Ashley Dreyfus’ Atomic Man, a groovy, bell-bottomed hero, or Robert Palacios’ Giant Man’s Day Off, a charming portrait of the Marvel icon as luchador (this and several other pieces reminded me of artists like Mark Ryden or Ivana Flores who traffic in subversive neotenic cuteness, a common enough approach nowadays). Overall, techniques on view range from rubbery cartooning to airbrushed polish, from precisely rendered surfaces (again, Slater) to frenetic painterly smudging.

(Images below of individual artworks are from coreyhelfordgallery.com unless otherwise credited.)

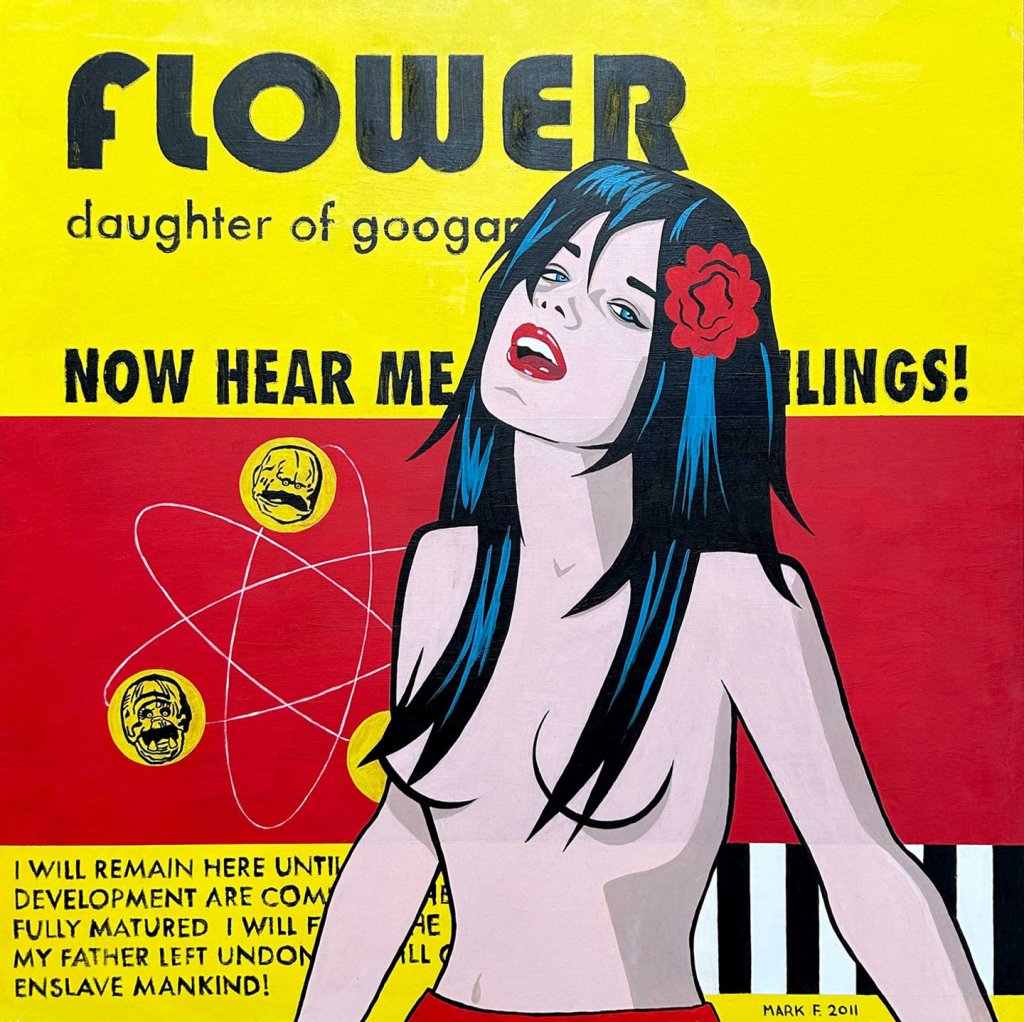

Many of my favorite pieces here depart from the Kirbyesque, or do Kirby style in odd, left-field ways that I find refreshing. These would include the life-size Dr. Doom Mask (acrylic on sculpted cardboard) by artist Nonamey; the canvas Five Cents, by Shaky Kane, which turns Kirby’s Captain America into an outsize bubblegum card; and Mark Frauenfelder’s Flower, Daughter of Googam, which bizarrely combines Flower, Kamandi’s near-nude wild-child love interest, with references to an early-1960s Marvel monster.

For me, one of the coolest spots in the show juxtaposes Mark Badger’s lively drawing Julius Caesar’s Ghost Appears to Brutus (a spinoff from his Kirby-inspired Caesar comics project?) and Sydney Heifler’s enigmatic digital print Rising, a dark, obscure image in which points of light (like glowing pegs on a pegboard) form a figure rising from two cupped hands, in a seeming homage to the Silver Surfer rising from the hands of Galactus. These are very different works, but their one-two punch delighted me (dig the big hands!). I’d say look out for odd moments of connection or contrast like this throughout.

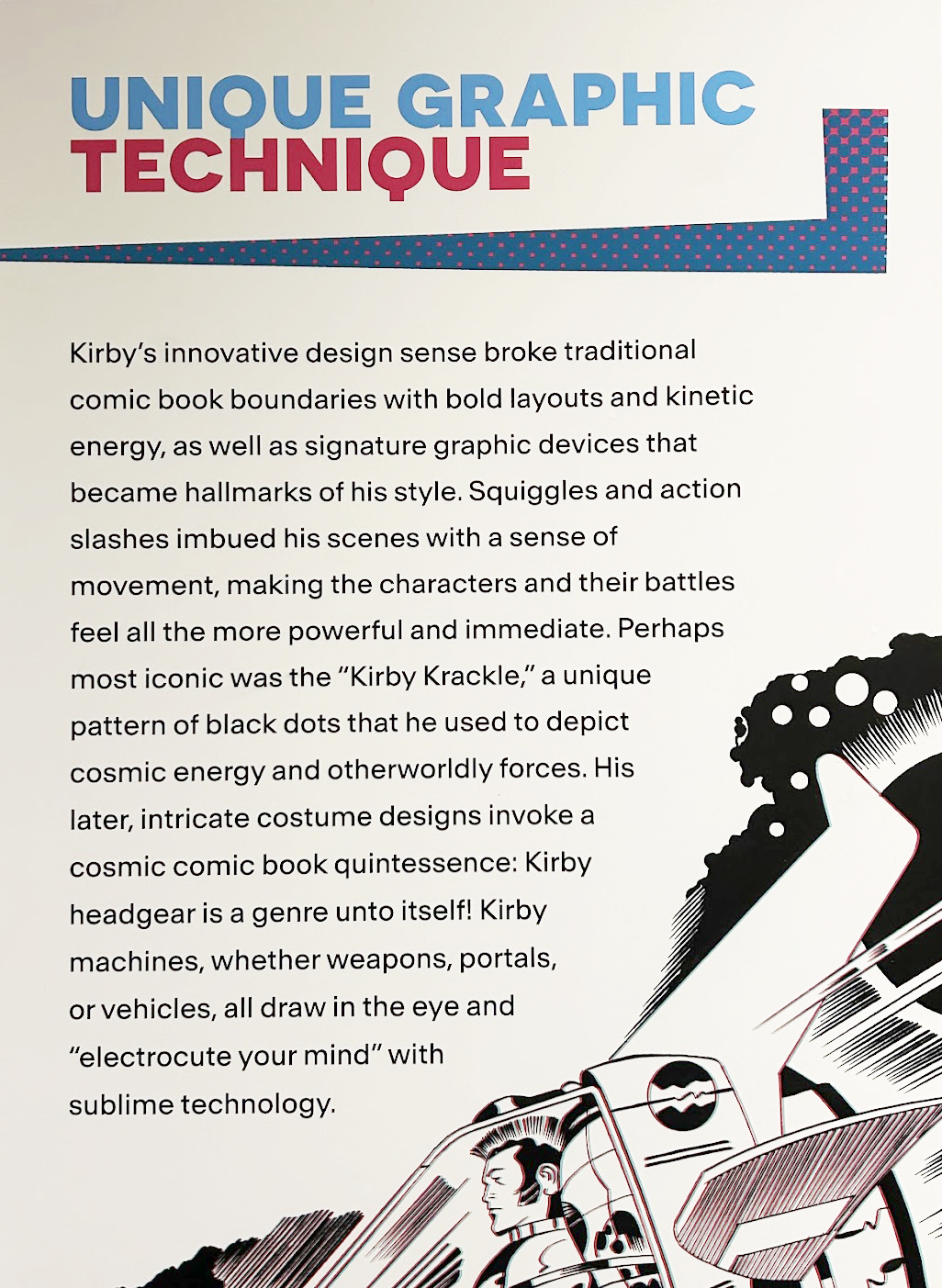

Besides paying tribute to Kirby, Kirbyvision contextualizes Kirby himself via a side gallery of Kirby originals organized by the Kirby Museum (the art on view in this side gallery, note, is not for sale). This is a smaller space, but dense with art and information. It feels distinctly museum-like, in the sense of didactic, yet also welcoming and visually sumptuous, building on the Museum’s track record of accessible pop-up exhibitions. Wall-mounted blurbs, succinct and informative, guide visitors through Kirby’s career thematically rather than chronologically. Newcomers to Kirby can learn a lot here about his graphic style, storytelling habits, range of genres, and famed titles and characters. The emphasis is on Kirby’s handiwork and the outpouring of his sensibility, not on corporate-owned IP (though there is plenty about that too).

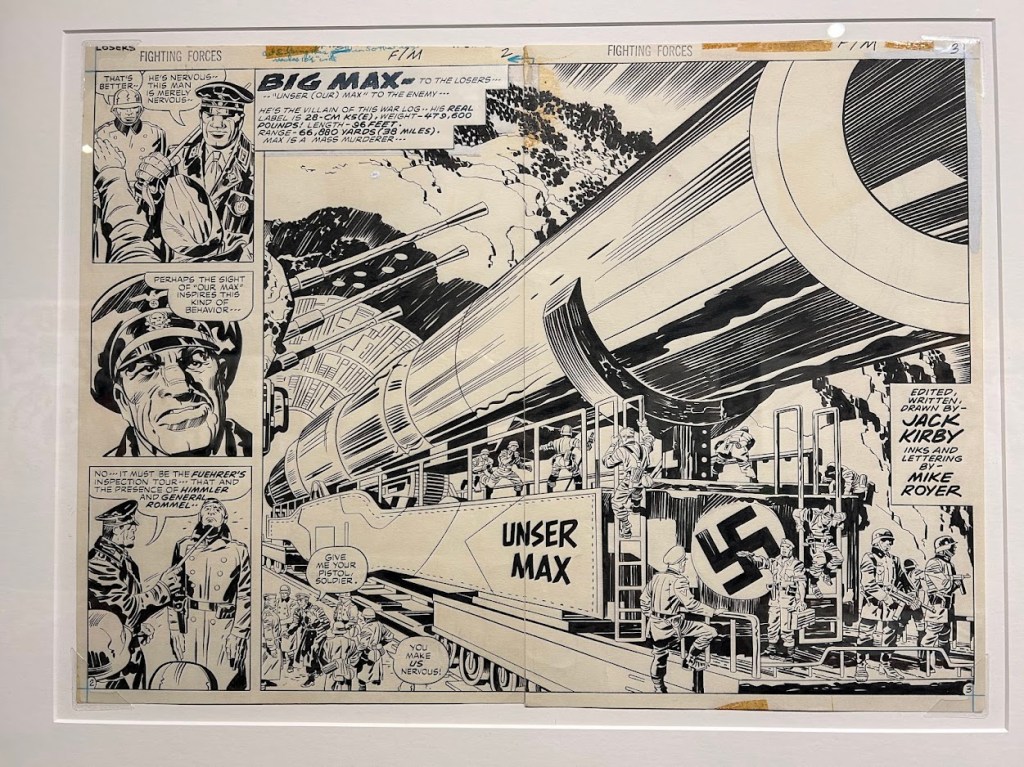

The originals, nearly fifty, are juxtaposed with reproductions of penciling process and, at the same time, images showing Kirby’s influence on screen adaptations (including the Marvel Cinematic Universe). Putting Kirby’s autographic work next to reminders of these adaptations feels like a deliberate strategy. One long wall represents well-known Marvel IP, including Captain America, The Fantastic Four, Thor, The Hulk, The X-Men, and The Avengers, while facing walls and tables lean into Kirby’s personal style and themes. The range of work shown, from 1940s to the 1980s, and from drawings to collages, suggests the arc of Kirby’s career. The genres sampled are many (and sometimes blurred), from superheroes, science fiction, and myth fantasy, to romance, crime, horror, and war. Many facets of Kirby are on display: his futurism, but then again his primitivism; his rapturous psychedelia, but then again his hard-hitting, lived-in urbanism. Various eras and collaborators are represented (among the inkers, I counted at least Dick Ayers, D. Bruce Berry, Vince Colletta, Frank Giacoia, Mike Royer, Joe Sinnott, Chic Stone, Mike Thibodeaux, and Kirby himself). Most importantly, this exhibit suggests something of Kirby’s outlook and spirit.

I spent a lot of time in this historical exhibit, digging pages and spreads from, for example, Kirby’s Fourth World, 2001, “The Losers,” Kamandi, and In the Days of the Mob; three of his collages (2001, Spirit World, Captain Victory); contrasting Thors, inked by Ayers and Colletta respectively; a beautiful vintage page from “Just No Good!” (Young Romance #18, 1950), which I took to be mostly inked by Kirby; and on and on.

Another highlight of the side gallery is the presence, on four tables, of oversized facsimiles of Kirby comic books, complete with advertising and editorial matter as originally published. Tom Kraft, Kirby Museum President and design wizard, has been producing facsimiles like these since Kirby’s centennial in 2017. Scanning old comics at ultra-high resolution, he and his colleagues then print and bind them as enormous, durable books that visitors are welcome to flip through and read at leisure. These giant books cross the gap between comic art designed for reading and the more spectacular, scaled-up experience we typically expect in museums and galleries. They make it possible to see Kirby’s work up close as if you were a small child just learning to handle physical comics (their scale is both delightful and daunting!). On this occasion, the Museum has provided 17 by 22-inch recreations of Captain 3-D #1, Young Romance #8, Fantastic Four #48, New Gods #7, and Our Fighting Forces #152. I like this mix of famous and more obscure works. In addition, and this is the pièce de resistance, there’s a gigantic, 22 by 30-inch version of Kirby’s adaptation of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. This gets a table unto itself, which is good, because I spent a long time admiring its bombastic pages—some of which Kirby himself colored, in saturated, psychedelic mode. I’ve always liked the idea of exhibiting comic art in poster-sized yet readable form (an unfulfilled dream of mine for Comic Book Apocalypse), as it brings immediacy and accessibility to the gallery experience, and it’s great to see the Kirby Museum pulling this off.

Immediacy and accessibility characterize Kirbyvision as a whole. It’s a hardworking, vivid, extravagant show that captures some of what is wonderful about Kirby, as well as his galvanic influence on comics and culture. Everyone who spends time with it will come away with different observations and favorites. Kudos to the Kirby Museum and thanks to the Corey Helford for making this happen.